The Winter's Tale: a beautiful message

The Winter’s Tale, currently in production at Studio 58, is supposed to be one of Shakespeare’s “problem” plays.

The problem being that it starts off like a tragedy and then about half way through turns into a pastoral comedy. This is only really a problem for librarians and system-obsessed academics. For anyone interested in theatre as performed text, The Winter’s Tale is an intriguing challenge. Personally, I think it’s one of Shakespeare’s attempts at synthesis, a conscious mixing of forms and, looked at this way, has a strangely contemporary feel to it; with its shifts of tone it can be thought of as sort of like a Cohen brother’s film.

Not that The Winter’s Tale isn’t without its problem and that problem is that Leontes who – in the tradition of Shakespeare’s great tragic heroes such as Othello, Lear and Hamlet – has to act like a turd in order for the plot to kick into gear. In this case, Leontes (Mike Wasko), the king of Scilly, thinks that his missus, a heavily-pregnant Hermione (Melissa Dionisio), is cheating with his old buddy Polixenes (Jason Clift), the king of Bohemia, who has been hanging around Leontes palace for sometime (long enough in fact to have put the bun in Hermione’s oven). Leontes fears are so baseless and his response so extreme that it’s all rather implausible. Thankfully, Wasko delivers such a strong, grounded performance that Leontes’ whip-snap change from doting husband to jealous wreck to mourning self-flagellator is practically seamless. This is high praise indeed.

As for the problem of genre, Anita Rochon does a fantastic job of navigating the rocks between tragedy and comedy. In fact, she does such a great job that this is the best Shakespeare I’ve seen staged in Vancouver since I returned here in 2001. In her understanding of pace – this production clips along as I think Shakespeare should - and in the actors commitment to the language (their interpretation of the text is almost universally crystal clear, ie none of them sound like they’ve got wool stuffed in their mouths), this is a lively, beguiling production.

Set in a Russian-inspired Scilly dominated by Wasko’s Leontes, the first half “tragedy” has a cool sophistication to it. While fully in the grip of jealousy, Leontes’ newborn baby is brought to him by a supporter of his wife, Paulina (Kirsty Provan – doing a forceful job as an “I told you so” Cassandra) but the king refuses the child, assuming it to be the product of Polixenes’ rogering of Hermione. He then orders Antigonus (James Elston) to take the child to some far off place and have it killed. If that wasn’t enough, he then publically tries his wife for adultery and finds her guilty – despite the fact that messengers (dressed as Cosmonauts) arrive from the Oracle and clear her of any wrong-doing. Immediately after the trial, we learn that their oldest child has died and that Hermione has also, allegedly, died of shock.

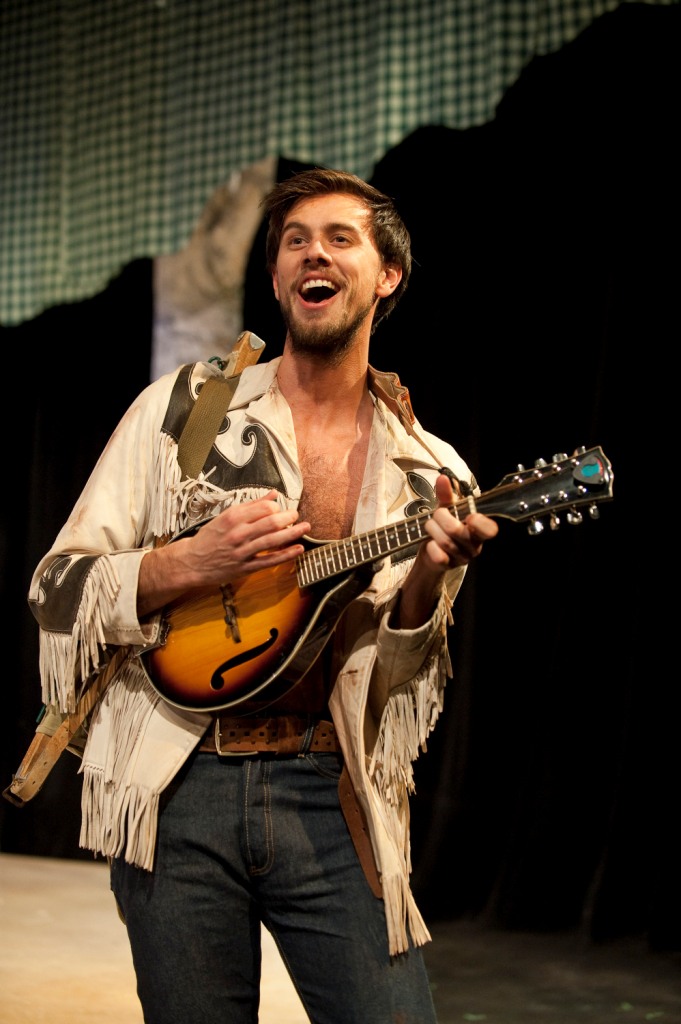

It is the newborn, taken by Antigonus into the forest of Bohemia, that traverses the two worlds of the play and Rochon handles this sequence beautifully. For his troubles, poor Antigonus suffers the most famous stage direction in English language theatre: Exit, pursued by a bear. After the bear (which is nicely judged in this production), we are alone for a moment with the child in its basket before she is discovered by a kindly shepherd (Byron Noble) and his son (Raes Calvert). We are then magically (and in this production cleverly) whisked 16 years into the future where we meet the grown up Perdita (Gill Roskies) who is in love with Florizel (played by Graeme McComb, who is, naturally, Prolixenes’ son). If the first half is dominated by Leontes and his strange behaviours, the Bohemian section is dominated by the machinations of Autolycus – a peddler/trickster extraordinaire - played with great joy by Benjamin Elliot. The clown work between Elliot, Calvert and Noble is quite exceptional and lifts the pastoral sequence to terrific comedic heights. Narratively, Autolycus’ machinations seem to lead him nowhere but it is a blast getting there with these three.

In contrast to the coldness of Russia (represented here by stripped bare trees in Christopher David Gauthier’s set), we are presented with a Bohemia that is all early ‘70s hippiedom. Despite the amazing costumes created by Marina Szijarto for both sides of the divide, I must say I was less sold on the settings of Cold War Russia/flower-child Bohemia. Although it successfully demarked the two worlds, it didn’t quite hang together for me as likely opposites – I couldn’t get the core message or how it supported the story – but really this is a minor quibble. The pastoral sequences are in themselves dazzling fun and for some reason Shakespeare’s comedies and flower-child aesthetics always mix well. Not to mention that the cast have a great time delivering sixties/seventies inspired business and tunes (as a side note, the music sequences contrasting the heavy choral work of the Russian world and the lighter Hippie world is extremely effective).

There has been much debate about why Shakespeare titled the piece The Winter’s Tale yet it seems rather obvious to me. Instead of being about the young lovers Perdita and Florizel, the focus of The Winters Tale is the middle aged Leontes and Hermione. Even the – for Shakespeare unusual – 16 year break between the two halves seems to emphasize the sense of loss (and lost time) that is a feature of middle-age relationships which have gone off the rails through misunderstanding. The true romantic heart of the work is not frustrated youth finally getting it on but rather on the reconciliation between older lovers – a love story that can only happen in “winter”. It’s not about happily ever-afters but correcting past mistakes and the possibility of redemption. The cold absoluteness of comedy and tragedy are blurred into something far more profound and human. It is at this point that Wasko really shines – the sense of joy at seeing his wife alive again is both palpable and true. Such emotional honesty on stage is, sadly, an all too rare a sighting in Vancouver. The final reconciliation between Leontes and Hermione (and then between mother and daughter) is so beautifully realized by all the performers that I had to stop myself from having a bit of a weep.

I think there is a message of hope in this play that Rochon and her team have beautifully and skilfully illustrated. From the child in the basket – the tragic world being transformed into the comic – through to the final reveal of the still living Hermione, it is a play that shows that we can all have second chances (even misguided turds) and that the things we’ve lost can once more be uncovered.What greater message could you want on a rainy November night in Vancouver?

If you ever acted stupidly in a relationship, if you’ve ever lost the one you loved, go see this play. It has something to say to you.

The Winter's Tale continues at Studio 58 until December 13. Seek more information here.