A Streetcar Named Desire: a cinematic experience

Stella!

I just had to shout that.

Has there ever been such a fusing of a single performance to a single character as Marlon Brando with Stanley Kowalski? Has there ever been a review of Streetcar Named Desire that doesn’t talk about Brando? Has there ever been an audience that doesn’t wait for:

Stella!

I’ve seen productions of Streetcar Named Desire which have theoretically gone back to Tennessee Williams' original “intention” with the character and still the ghost of Brando hovers over the proceedings. The movie is so powerful, so iconic that it trumps everything including the usual forms of transmission that one would expect for a stage play. When a production of a hit play from New York or London lands here, we are able to see it free of any expectations and simply let the Vancouver-based artists do their job and interpret the work. When you do Streetcar, you’re not just interpreting Williams, you’re invoking the electric ghosts of Brando and Vivien Leigh, Kim Hunter and Karl Malden; more than anything you’re managing audience expectations fuelled by the film, including, most of all, Brando’s performance and his t-shirt.

Stella!

In a sense, Leaky Heaven embraces this dilemma with a production (really more of a formal experiment) that owes as much, if not more, to the film than to the original play. By doing so, it explores the motifs and language of film and by further extension notions of how the experience of watching a film is, itself, inherently fused with an unconscious sense of voyeurism. This then folds quite neatly back onto ideas of how naturalistic, fourth wall theatre itself provides a form of voyeuristic experience. When those well-heeled New York audiences saw the premiere of Streetcar back in the late 40’s, wasn’t part of the excitement in seeing the unrepentant sexuality and violence of the working classes sprawled out for their delight? They were glimpsing what they normally could only imagine.

When I say this production was an experiment, I really mean it. The entire show takes place inside and in the immediate surroundings of a small house on Woodland Drive. The house sits at the back of the lot of a bigger house (it’s basically where you’d expect the garage to be, with one side of the house facing the alley). The audience watches the entire show from either the street or the alley and moves around as they follow the action as it moves from room to room (well, for us, from window to window) until the performers spill out onto the street.

Long sequences take place inside the house, particularly in the dining room and Blanche’s upstairs bedroom. As we watch them through the windows, the actors’ voices are broadcast outside along with the sound of footsteps and the clunk of whiskey bottles in a sort of found version of movie foley-effects (that is, the sounds we normally don’t hear in the theatre). Viewing the action through the frame of the window immediately references the experience of watching a movie screen – while reminding us of moments (whether sought or thrust upon us) of witnessing our neighbours living their lives. The cinematic referencing (and framing) expands out into a spectacular, final conceit that I’ll get to in a moment.

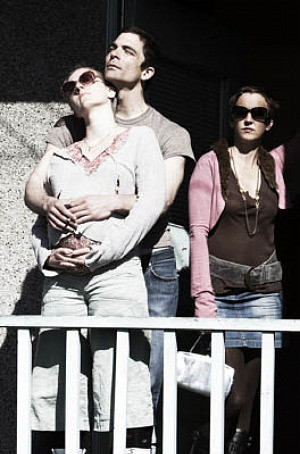

The frame is broken when the characters move outside and these are amongst my favourite moments of the evening. The famous “Stella” scene happens in the yard between the two houses, with Stanley (Billy Marchenski) yelling to an upstairs balcony. A hot and heavy reconciliation scene between Stella (Sasa Brown) and Stanley starts out in the garden and then moves back into the internal spaces of the house and the birthday party takes place out in the alley, with the audience surrounding the performers. Blanche’s (Lois Anderson) date with Mitch (Sean Marshall Jr) involves them driving backwards up the alley and back again. The yelling – Stanley and Blanche, of course – takes place outside and these puncture the cinematic framing device with moments of authenticity. I was immediately reminded of hearing neighbours fighting and screaming at each other, in particular of twenty years or so ago having to listen to the repeated, shouted lament from one woman of “I love you, Tina, I luvvvv you”.

Despite these moments of authenticity, director Steven Hill and his collaborators are not particularly interested in the emotional realities of the characters or the connections the audience might have with them. In fact, one of the themes of the evening is distance, of pushing the audience out of the narrative. Williams is an interesting choice for this sort of experiment. The real impact of his work comes not so much from his ideas but from the fragile, emotional breath he gives to his characters. The story of Streetcar is set very much in a specific emotional landscape. To post-modern eyes it might seem raw or overwrought. Because the emotional world of the characters is truncated (literally as some scenes are described by voice over and others are sped up), I think you need to be familiar with the text to begin to get at the meat of what is being explored here. This is a very intellectual exercise that’s being executed.

That’s not to say that there isn’t some dynamite acting going on because there is within the frame that Hill has established. Marchenski provides us with a lean, hungry Stanley always on the edge of volatility. Despite his insecurities, Stanley is no idiot. He knows the score and we see that intelligence with Marchenski’s performance. I’ve always found Stella to be a slightly thankless role but Brown does nice work as the referee/peacekeeper who is perpetually being sent out for Coke. Anderson is quite possibly the most feral, most overtly horny Blanche ever and while she’s great to watch I found that some of this voraciousness out of sync with how I personally imagine the character although very much in tune with what I think Hill was trying to achieve with this project.

The show ends with a spectacular effect. The implied rape scene is relayed through a pre-recorded filmed sequence involving Anderson and Marchenski that is in turn projected onto the side of the house. The image (all point-of-view, naturally) starts out focussed on a single window and then grows until it covers the entire side of the house, using the wall as a giant screen/canvas. The effect is stark and beautiful and further extends the exploration of live/recorded performance as the actors stand at the back of the crowd and recite their lines to their own filmed images. We have gone from overhearing dialogue inside a house to the walls of the house somehow resonating out these memories. The performance is now for us directly, like a movie, rather than as moments we strain to hear and see.

I’m not quite sure what I’m supposed to conclude from this exploration – although I’m grateful that Leaky Heaven has asked the questions they have. The house in Williams' Streetcar is as much a character as anything and seeing it physicalized is intriguing to say the least.

Theatre companies hate it when reviewers mention the venue in a negative light (you know the sort of thing, the seats were uncomfortable, the theatre was too hot) but its inescapable with this show not to mention the lived experience for the audience. Part of the conceit, I’m sure, is for the audience to work to see the show, to catch glimpses – just as if we were really being voyeurs. Maybe I’m a poor voyeur but I did miss a great deal by poor body placement and my general reluctance to run along with a herd of people.

So, if you’re going to really take advantage of this production, I suggest you find your inner Stanley and fight to the front of the crowd. It will also help if you’re nimble, quick and somewhat short.

At the very least, make sure you’re at the fence for the scene with Stanley shouting out for his Stella. Marchenski wrestles Brando’s ghost with aplomb and that’s something no voyeur wants to miss.

A Streetcar Named Desire runs until May 22, for more information ride public transit here.