OrienTik/Portrait: staring into the heart of the sun

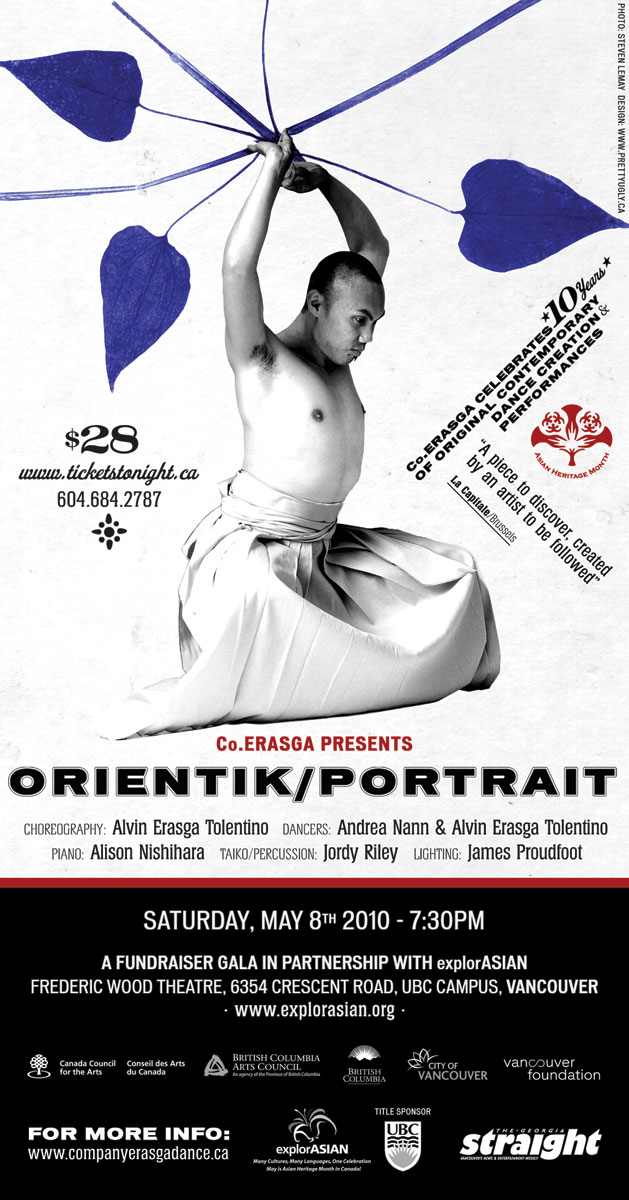

OrienTik/Portrait

For the opening night of the explorASIAN Festival on May 8th, Co Erasga performed OrienTik/Portrait at the Frederick Wood Theatre at UBC. The performers included dancers Alvin Tolentino and Andrea Nann and taiko drummer Jordan Riley. Piano player Alison Nishihara was absent due to illness. Even with recorded piano and some obvious silent gaps, OrienTik/Portrait remained coherent and moving. Composed of distinct images, driven by bold energy and clear intention, it was a work of aesthetic simplicity in the best possible sense.

The silent darkness of the stage was suddenly ruptured by the booming voice of a taiko drum. As the lights rose, the drummer laid down a persistent beat that thrummed like a small engine. Into this field of sound, two dancers emerged from the wings, a man and a woman each dressed in voluminous skirts, he in a vest and she in a cowel-necked top. The costumes were things of beauty -- pale, sand-coloured soft-sculptures with pleats and folds, that paid equal homage to traditional dress and high fashion. With measured steps, the dancers positioned themselves in squares of white light at the front of the stage.

Their movements expressed a fluid strength. They crouched in wide, martial stances, but turned deftly on the balls of their feet, circling around each other first one way, then the other. Their sharp, delicate hand motions (possibly meant to recalling Balinese dance?) seemed literally articulate – suggestive of meaning, signalling speech.

The duet gave way to solo performances, first by Alvin Tolentino and then by Andrea Nann. Tolentino's figure was a compact ball in a pool of yellow light: he crouched and rose and crouched again, opening and closing his body. Though the movements were simple, they were executed with a deep, inward focus, and the contracting muscles of his torso and chest were clearly visible. His arms rose gently and his trembling fingers floated in the air, as if vibrating to the sound of the drummer, who tapped his stick against the rim of the drum in a rapid stuccato. Tolentino turned his face ever-so-slowly up towards the warm light directly above. The mood was one of controlled joy – a notion that seems contradictory, except that Tolentino expressed these in equal measure – his movements were disciplined but light, strong but gentle. It was this harnessing of contradictions that made the performance such a pleasure to watch.

Nann's solo carried the same themes forward. There was a strength and purity of intention in the movements that expressed both deep calm and deep feeling. In contrast to Tolentino, whose body held clenched or quietly folded, she was a long, upright shape, a thin knife-like body moving at a diagonal through bars of white light. She would arc her torso way back, so that her sternum and heart pressed up towards the light. As she leaned back, her arms cut across her chest, and as she leaned forward her arms opened again. All the while, her body twisted delicately this way and that way. She took incremental steps, moving away from the downstage precipice and disappearing into the darkness of the far back corner.

Clean lines and strong geometry were the backbone of the work, a frame for the expressive movements of the dancers. In the same way, the taiko rhythms grounded the movements, and added texture and weight. The finale of OrienTik/Portrait brought the kinetic relationship between dance and drums to the fore: Tolentino and Nann entered a stage whose perimeter was laid out with evenly spaced individual cymbals on stands. Visually, these were impressive – gleaming in the stage lights, they provided dramatically a minimalist “set.” The dancers threaded their bodies around the cymbal stands, striking the plates with their finger tips. What began as a fluid arc, a pirouette with arms outstretched, would end with a sharp rap of knuckles against a cymbal's face. These subtle actions built to a crescendo that fused movement and sound, so that it was impossible to determine where dance ended and music began.

OrienTik/Portrait opened a limnal space, a borderland between aesthetic and spiritual experience. Movement was a kind of imminent sound, and dance the physical embodiment of music. Intangible feelings hovered in the air and were channeled through the figures that graced the stage. Watching Co Erasga's OrienTik/Portrait felt like staring into the heart of the sun – the work was so uplifting in its emotional brightness. It was a rare evening of performance.

Tags: