Four Quartets: eliot reinvented with talent and humour

Thank you Deborah Dunn for being so talented a dancer and so funny too!

Deborah Dunn presented four short choreographies, Four Quartets, as part of the Dancing on the Edge Festival; it was the last show I saw as part of the festival, and it was such a welcome highlight.

Each piece was based on a poem by T.S. Eliot, drawn from his collection of the same name. The poems are read while Dunn dances, and the effect is a lyrical interpretation of the poet’s elegant language. What Dunn manages to pull off in this work is a use of Eliot’s poetry that is neither pedantic not staid; instead she breathes life into the work adding humorous, playful even slightly cheeky touches amidst the seriousness that is Eliot.

Most of the poetry was pre-recorded and read by a man with a voice that is familiar and warm, yet sufficiently formal to pass for Eliot himself. What is lovely about Dunn’s work, however, is the fact that she absolutely does not allow the reading to drive her dance. Throughout the four pieces she is quirky and creative, gently subverting the language of Eliot as much as she plays to it.

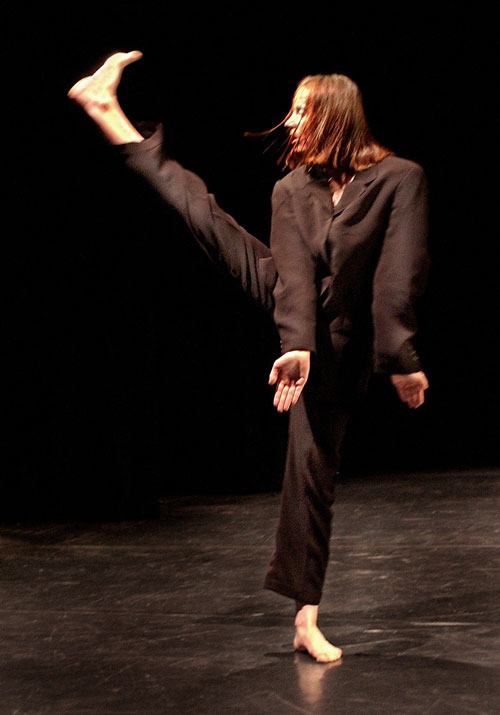

The first piece, Burnt Norton is lithe and graceful and showcases Dunn’s skill as a dancer and her ability to take up the stage with the utmost grace. Also impressive is the fact that she wears a slightly oversized men’s throughout the piece, yet still manages to appear elegant. Towards the end she pulls the suit jacket over her head to expose its bright red lining. As she sits with the pulled up jacket, I think she looks almost like a big red rose – brown on the bottom, almost scarlet on top.

East Coker has Dunn on stage in the same outfit, only in a piece that is somewhat more physical and the lights are brighter. There are moments of delightful humour as Dunn, at times, recites the poetry herself. In her recitation she sometimes seems to be asking the question, “Just what does this mean?” as, for example, when she lifts her head up from an elegant moment and recites the line “nourishing the corn”. She recites the line as if there’s a giant question mark, indicating the absurdity of these words in the context of her show. There are also moments of light comedy in her facial expression; from time to time she appears to be laughing at Eliot’s words while at the same time beautifully bringing dance to his words.

The comedy heightens in the next piece The Dry Salvages when Dunn reveals that beneath her brown suit pants is a rather scandalous red, lacy thong; she pulls her pants down just enough to show her undies. She remains in this pose long enough to make me think she’s having a good laugh as she moons the audience for a few seconds towards the end of this piece. The great thing about this and other moments like it is that Dunn is so clever at working these instances into her dance and weaving them deftly into the poetry that the result is not at all gimmicky or attention getting. Rather her emotional range from comedy to seriousness is entirely authentic; I get the feeling she really knows and loves the poems she dances to and has mined them for their full possibility of meaning and she has done the work to interpret them fully.

The final piece Little Gidding has Dunn enter the stage in a neutral coloured unitard with only flowers across her chest for decoration. This costume reminds me somewhat of the image of her with the suit jacket over her head, a return of the flower motif, which fits nicely with Eliot’s description of nature in his work.

In Little Gidding, Dunn recites the poetry herself, showing her full range of abilities as a performer. After the beginning, Dunn momentarily leaves the stage and re-enters wearing a scarlet skirt with massive Marie-Antoinette style panniers. With the warm lights and the rose petals that she leaves strewn on the stage, I almost felt like I was being invited into an English garden on a summer’s day; but the show is nowhere near as cliché as that.

Instead of giving into the impulse to be entirely Eliot-esque, Dunn turns the panniers of her skirt so that they are in front of and behind her; she grabs hold of the one in front and appears to ride the panniers as though they are a hobby horse. She then trots around the stage. Eventually, the skirt comes off after the recitation of the line “The Beginning is often the end”, and the poetry returns to voiceover as Dunn prepares to find a graceful end to these four pieces.

The last line of the final piece is “The fire and the rose are one”, and I have the feeling that what Dunn has so successfully managed to do is a delightful and skilled blending of the arts of dance and literature. Add to that intelligent lighting and playful, creative use of costume, and I’d have to say that Dunn’s show was an entirely lovely piece of work that drew me into a very imaginative world where the finely wrought words of Eliot were beautifully enlivened by Dunn’s creativity, talent and wit.

The Four Quartets, by Deborah Dunn, produced by Trial & Eros was part of this year’s Dancing on the Edge Festival.