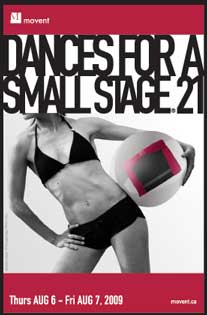

Dances for a Small Stage 21: from nutcracking to polemics

Vancouver: Dances for a Small Stage 21 proved to be another strong and eclectic installment in the wildly popular dance series.

Slow Burn

Choreography and performance by Burgundy Brixx

An experienced burlesque dancer whose career found its feet in New York City (or perhaps, to be accurate, lost its feet but found other more interesting positions) Burgundy Brixx brought sass and swagger to the Legion on the Drive as the opening performance of Dances for a Small Stage 21. Slow Burn is a comic riff on the image of the stripper who's seen it all, with Brixx striding onstage in tailored black pants, a black tuxedo shirt and black pumps. With a cigarette dangling from her lips and a lone bar stool draped in a red table cloth as her props, she slugs back straight shots of vodka before whipping off her tear-away clothing with a blunt sexual machismo reminiscent of shock-rocker Peaches. In the white spotlight, her wine-red lips accentuated her pale skin. Covered only by a black G-string and pasties, she makes lazy gyrations around the stage. Then, with a sideways smile at the audience, she extinguishes her cigarette on the tiny protective covering on her right breast – as if to say Honey, there's nothing you could ask for that I ain't already done before. Deftly lighting another smoke, she prances out of the light and off the stage.

Vexed

Choreography and performance by Julia Zennström

Julia Zennström showcased her physical skill and precision in this work, designed as “a study of solitude, frustration, and determination.” Dressed simply in a tank top and bicycle shorts, the emphasis is on movement rather than narrative. Zennström makes full use of the stage, moving to each corner as she builds her vocabulary and fleshes out her concept through movement. She comes across as focused and athletic: her motions are reminiscent of skiing, climbing, lifting, and otherwise conquering a vast solitude with one's body. The premise of the work and Zennström's execution are expertly matched: what Zennström promises she delivers.

Make Room

Out Innerspace Dance Theatre

Choreography and performance by David Raymond and Tiffany Tregarthen

The challenge with duets, perhaps more than solo or group dance, is to make the dynamic between the performers fresh. Often a couple will be situated as lovers, competitors, or friends but beyond these literal and obvious pairings what can two bodies say to an audience? How do they interact, and what brings them together, aside from the obvious conventions of dance?

In Make Room, Raymond and Tregarthen offer a subtle reconfiguration of common pairings. When the lights rise they are intimately entwined, and the closeness of the pose suggests erotic attachment. They are low to the stage, straddling each others' laps, in a posture that must require enormous strength to hold. They unwind and move in unison around the stage, echoing each other exactly. As they move, the warmth of their early embrace slowly dissipates; their movements become restrained and their relationship becomes distant and cold. The music builds anticipation, rising to a crescendo, but the energy between the dancers does not rise with it. The distance between the music and the dance suggests unfulfillment, disappointment. It is as if, in the fictional universe of this piece, we have been invited to witness a romance, but instead we have witnessed an invisible emotional break.

Through of very different physiques, Raymond and Tregarthen are closely matched for height and when they move in unison, they mirror each other convincingly. The significant discrepancy in their movements lies in the way that Tregarthen often reaches out to touch her partner, assertively moving his head and shoulders. It is as if she is asking a silent question over and over, one that he consistently refuses to answer. Why are you here, she seems to ask, and how far can I push you? He stares passively off stage, frozen and unable to respond to her questions.

The effect is that the initial romantic premise of the work is spun in an existential direction. Raymond and Tregarthen read not as lovers but as partners in a quest for meaning that can only be satisfied each by the other. Perhaps in the final analysis it is a tragic story that they perform, for if she is asking a question, he gives her no answer.

In terms of technique, Raymond and Tregarthen are subtle and lovely. Hints of jazz and hip hop are woven seamlessly into a performance whose overall tone is far from the celebratory roots of these forms. Make Room proves that substance trumps style, as the dancers show their skill in referencing these traditions in the context of their own melancholy imaginings.

Disappear; You Knocked Me off My Feet; Chante-le a Tes Dents Serrées; and others.

Music by Owen Belton

By providing musical interludes on guitar Owen Belton changed the pace at various points in the evening. A successful moderator, Owen kept feet tapping and faces smiling while costumes were changed and sets were shifted. His folk inflected pop-rock is heartfelt and understated and his stage banter charming and direct. He offered thanks to various supporters, slipped in a few background stories about his songs and managed a plug for his latest CD, all within the limits of the time allotted between dance performances. For a sample of his work check out his myspace page.

The Nutcracker

Creators/performers: Lesley Ewen and Billy Marchenski

An entertaining piece of physical comedy, The Nutcracker pokes fun at the beloved work of the same name. Marchenski enters as the Nutcracker, moving woodenly, falling over onstage and hoisting himself upright on stiff legs. His face is painted white with round patches of pink on his cheeks. He is garbed in white stockings and a red soldier's jacket. All dressed up and no place to go, our classical hero falls disconsolately to eating peanuts (he nods and mimes to the audience: NUT-CRACKER, while crunching on the shells). His glum reverie is interrupted when a cleaning lady arrives pushing a broom and begins feverishly sweeping up his scattered shells. He gazes at her in astonishment and then turns the tables, sweeping her up in his arms, anointing her as his fairy princess.

When the cleaner appears nonplussed, the gentlemanly Nutcracker immediately divines the source of her disgruntlement – she is not dressed for the part! He produces a tiny white frock and daintily attempts to dress her as if she were a two-year-old. When the girlish tutu will not rise above her woman's hips, the Nutcracker can only shake his head in confusion – this is not how the magical story is supposed to unfold. Struggling with the shocked lady's clothes, he suddenly realizes – aha – that there is a face painted on her midriff. The two begin to waltz, the Nutcracker gazing earnestly at the woman's made-up belly.

At this point in the story, members of the audience were splitting their own guts with laughter. Short and to the point, the piece sketched its source material in a nutshell, as it were, with enough accuracy that its gags hit the mark. By the time the lights fell, audience members were hysterical with amusement and all but picking themselves up off the theatre floor.

Drift; a little urban fairy tale

Choreography and performance by Yannick Matthon

Hell hath no fury like an artist scorned – a modern truism that politicians would do well to bear in mind. Drift; a little urban fairy tale takes aim at capitalist greed in general and at politicians who make cuts to the arts in particular. Matthon arrives onstage in a shipping crate and comes tumbling out in a sea of foam packing peanuts. In a charming Quebecois accent he explains that in these tough financial times it is the best he can do for accommodation, and what's more its cheaper traveling as freigh. He then launches in to an extended diatribe against everything from 21st century pollution – claiming to have floated in to town by way of the garbage patch in the Great Pacific Gyre – to Stephen Harper's ill considered budgetary reforms to the arts.

Matthon, dressed in a paperboy cap and a giant T-shirt with a gold money symbol sewed to the front, looks like a cross between Oliver Twist and a homeboy. As he rants, he slips behind a curtain, strips down to a tank top, and hoists the T-shirt like a flag over his makeshift house, adding a small pirate flag at the top for good measure. Continuing his speech, he pulls a letter addressed to Stephen Harper from his pocket that demands the reinstatement of arts funding. He calls on the audience to sign copies placed by the theatre door.

Finally the music rises, and Matthon begins to dance, using the interior of the shipping crate to frame his movements. The rap he performs continues the social discontent of his speech. Over-top of ominous beats, the lyrics references the war in Iraq and the vacuousness of pop culture. Matthon's dancing is some of the most skilled of the evening: he has fine internal strength and control as he contorts himself in and around the shipping crate.

Although Matthon's social commentary was timely and much-needed, he is such a talented dancer that I was left wishing that he had given more time to movement and less to grandstanding. Ideally he would have integrated speech and dance more fully, so that one could have enhanced the other.

Strathcona High Class of '56

Choreography and performance by The Contingency Plan: Vanessa Goodman, Jane Osborne, and Leigha Wald

At once hedonistic and merry, this piece was a prime example of storytelling through movement rather than words. Accompanied by the Bobettes, three women in pastel dresses, be-ribboned and wrapped in bright satin like party favours break into a finely choreographed selection of 1950s dances, from Bop to Jitterbug. They are a delight to watch: as they deftly paraphrase the movements of a bygone era, one can clearly see the patterns of past social mores. The girls are prim and ladylike as they enter. When they dance, they are suddenly both coy and brash – flashing their bloomers, shaking their hips, and bouncing lightly over the stage. Hindsight is 20/20, and in this piece we can clearly see the ways that female sexuality has been socially managed. The girls mince shyly to the edge of the stage, and with bashful waves and fluttering eyelashes, they entice two men from the audience up to dance. Suddenly the two partnered girls are prim again, cuddling with their men, but then backing off to remain at arm's length, as they try to navigate between what is good behavior and what feels good.

The third dancer, unable to find a partner, becomes disconsolate. Angrily, she strips off her ribbons, pulls the padding out of her bra, and then wilts into a ragdoll pose. The other girls shoo their men away and then mime excited gossip to each other, until they notice their companion. The music shifts, and the three figures start to dance in poses that are both sultry and aggressive – the very image of thwarted desire. As the music intensifies – moving from Elvis into the Breeders – so does the dancing. The women's poses become increasingly suggestive, wilder, and more uninhibited. By the time Fleetwood Mac comes in, the once dutiful daughters have become wild Bacchantes. Stripping down to their lacy underthings, they storm in a circle around the stage, beating on imaginary drums and shaking imaginary horns, like wood sprites or Shakespearean witches on a heath. The piece was an audience favorite, and the performers left the stage to whistles, hoots, and wild applause.

On Any Given Day

Choreography and performance by Justine A. Chambers

A contemplative, gorgeously choreographed piece, this suffered slightly for its placement in the program. After the successful blend of energetic Strathcona High Class of '56, it was difficult as an audience member to come down to earth for the restrained and introverted On Any Given Day.

That said, this was clearly a work of great skill, a dancer's work of dance and it deserved an attentive audience. Incorporating a complete range of movement, from the mechanical and spastic to the fluid and graceful, Chambers proved that her body is her instrument and that she knows how to play. She made little use of the floor, focusing instead on upright postures. These covered everything from traditional pirouettes and leg lifts, to more modern poses – bends and squats that emphasize the athleticism of a body as much as its grace. Her motions were finely tuned – the angle of her wrist was as important as the placement of her leg or torso.

Set to a mystical score by Sufjan Stevens, On Any Given Day comes across as a studied work in the best possible sense: it is not narrative rather about the relationship between the dancer and the music. Chambers' choreography is complex and exacting, and one senses that she never loses sight of her intentions during the performance. Though there is plenty of detail her work, there is no extraneous movement, no frills and no fluff. Every gesture is reasoned, weighted, and placed just where it needs to be.

American Idiot

Choreography and performance by Burgundy Brixx

Brixx returned to close out the evening with more burlesque tomfoolery. American Idiot saw her dressed in every permutation of the stars and stripes imaginable, from the glittery bow in her hair to the toes of her spangled stilettos. Her dress was comprised of a shiny bustier and individual small flags over yards of tulle. She stripped these away to the raunchy strains of Green Day's American Idiot, and each gesture revealed a tiny cap gun that she would brandish suggestively at the audience. Finally, when she had stripped away all the flags and tossed away all the guns – jiggling her body with hysterical vigour – she removed the skirt and top to reveal a sequined miniskirt and star-studded bra. Just when you thought Brixx had nothing more to take off and nothing more to hide, the miniskirt fell away and she drew a gun from her bikini, while John Lennon broke in singing happiness is a warm gun.

I know folks who've gone sour on burlesque, saying “we all know how it ends.” Brixx proved them wrong. Her last act was not to take off another item of clothing (though in fact the bra did come off), but to shoot herself in the chest with the cap gun and fall to the floor in melodramatic death throes. Lennon's warm voice faded out and past-NRA president Charlton Heston's voice cut in with the infamous line “from my cold dead hands.” Brixx continued to shake on the floor, and one suspects that this was not so much for the sake of verisimilitude as because she couldn't contain her gleeful laughter.