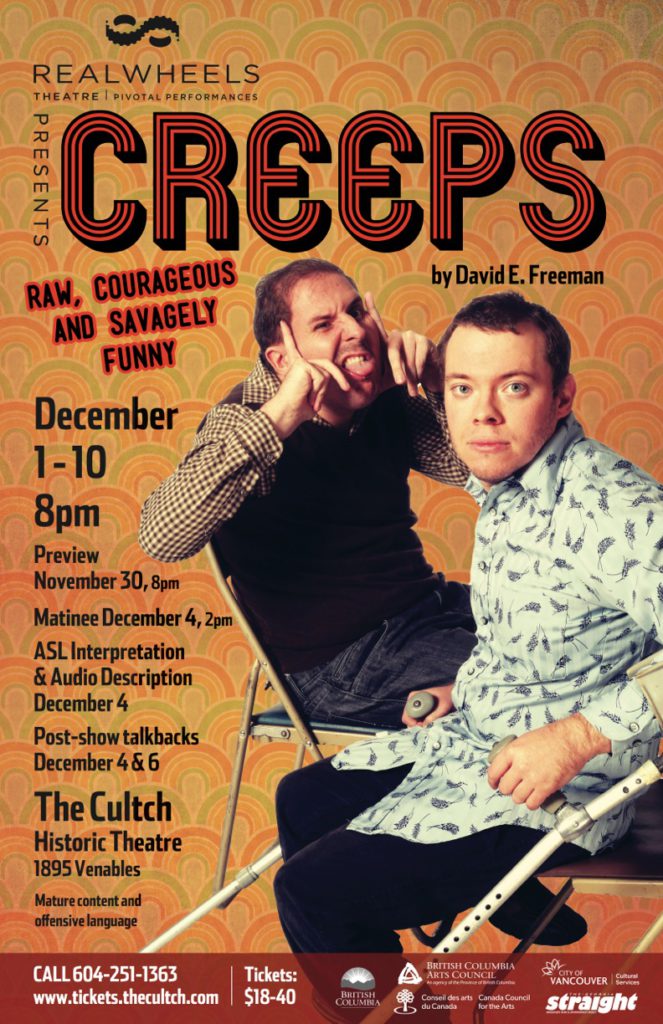

Creeps - Depressingly Funny

Freeman’s 1971 classic is well presented in the spare but perfect space of the Cultch’s Historic Theatre. Anyone familiar with early 70’s rundown institutional design and maintenance should viscerally respond with phantom aromas of the vintage nicotine colour palette and poorly maintained porcelain and badly procured paint and cleaning supplies. The set design, faithfully detailed by Lauchlin Johnston, wafts off the stage to create the perfect hopeless venue for institutional hopelessness and despair, seemingly only steps away from the realms ruled by the monarch of orderly sadism, Nurse Ratched. There is a Godot-like quality to the explorations of the dreams by the four main characters. Aaron Roderick wonderfully portrays Tom, who has truly given in to the weight of the system that both maintains and slowly crushes him, which he secretly knows, but appears too afraid of the unknown to fight against. He is the spastic equivalent of Dilbert’s Wally, they guy who sees no point but getting whatever benefits are available from the system he is enmeshed within, at the minimum amount of effort. David Kaye’s seemingly bit part of Michael, the innocent touchstone, for whom flushing water brings simple delight, even though it has and continues to bring negative consequences to him, perfectly delivers the character’s innocent stooge to the stage, incriminated by proximity of the institution and his need to belong. Pete, the struggling to have self-belief in his art, and eloquently portrayed by Paul Beckett, almost makes the case that, perhaps now, but not really in 1971, someone with his dream could almost make it out in the real world. The slang term Spaz was something that was as common in my childhood as dude or bitch is in today’s world, though possibly with more social weight to the term.

Brett Harris’s Sam, wheelchair bound but otherwise practically normal in his venality, cynicism and opportunism, becomes the seeming antagonist which rallies the other main characters to discuss why they haven’t pursued their dreams further than continuous longing in discussion and minor dabbling. He pushes the other characters to give their reasons, form alliances against his hectoring, and otherwise keeps things moving. Wheelchairs are good for that. Jim, Adam Grant Warren’s incredibly physical portrayal of the golden boy of the shelter, the one who has more ability, more influence with the powers that be, is a deeply embedded agent of change, who perhaps dreams of being a force for good to his comrades, yet somehow seems more embedded and changed through his comfortable role as aide to the system rather than change agent to affect lasting improvements for himself and his comrades.

Miss Saunders, the supervisor who can’t seem to manage her own prurient imagination much less a cadre of resistant exploited other-abled workers, as portrayed by Genevieve Fleming, delivers just the right amount of comedic irritation to rally the resisters in their common cause; being pissed off at the systems that pigeon holes them, exploits them, and benefits from the social credit of helping the poor afflicted. When she can’t badger or whine enough to get compliance, always leans on the background authority of David Bloom’s ever so confident Mr. Carson, the authority of policy, of reasonable power, carefully cloaking the boundaries of perception that maintains the illusion of benevolence over the steel wall of inevitability. Of course the workers will comply. The system demands it. Society demands it.

This is a gritty, depressingly funny piece, and which reveals as much to this author about the current world as it does about the period in which it was created. The show runs until December 10th, so if you are looking for something that isn’t seasonal pantomime, and speaks to our current realities, check out Creeps.