Bone in her Teeth: The Discreet Charm of the Cannibals

Of course eating people is wrong. But sometimes it’s necessary.

Our social and evolutionary conditioning is so deep that when imagining possible cannibal scenarios for ourselves – a plane crash in the Andes, say – we like to believe we’d starve before eating a fellow passenger. Yet, looked at rationally, if we were starving and meat, whatever its source, was just lying there, why shouldn’t we eat it? Why can’t we see that left leg as just a piece of meat rather than a piece of Kevin?

The tension between social conditioning (our human selves) and raw hunger (our animal – and perhaps true – selves) is at the core of Bone in Her Teeth, Leaky Heaven’s latest production. The threat/promise of cannibalism is thick in the air of the performance space they’ve created on the stage of the Russian Hall. Befitting their circus roots, Leaky Heaven creates the feeling of an intimate carnival of horror.

Bone in her Teeth is based on the true story of the survivors of the Medusa, a French naval frigate that sank off the coast of Senegal in 1816. While the first class passengers and crew were loaded into the relative safety of lifeboats, 150 lower class passengers were dumped onto a makeshift raft. After only six kilometers, the lifeboat passengers cut the rope to the raft, abandoning the poor souls to their fate. The story inspired Theodore Géricault’s iconic painting, The Raft of the Medusa. It is this painting with its terrible pile of desperate bodies which was the main inspiration for Leaky Heaven. It is wonderfully evoked at the end of the piece with a tableau mixing of actors and pieces of broken mannequins.

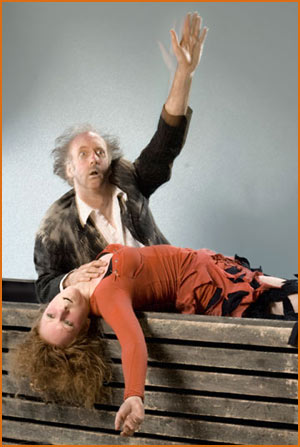

Back in 1816, the living ate the dead to survive. Not unlike a horror movie, Bone in Her Teeth builds to that inevitable moment when one of the passengers will end up as dinner. You know it’s coming. You immediately start sizing up the options presented to you, choosing from the ensemble of four archetypal characters played by Peter Anderson (a tramp-like businessman), Sasa Brown (a tramp of another type), Billy Marchenski (an obviously out-of-favour officer) and Tanya Podlozniuk (an out-of-sorts Russian). My money is on the unhappy Russian.

Like any good horror story, Leaky Heaven keeps the horror at bay until towards the end. When the cannibalism does arrive, it is not one of the passengers that makes the first course but a succulent baby that Brown has managed to secure for herself. In a fantastic piece of physical humour, Brown deftly plays with the competing desires of wanting to cradle the baby (the socially-dictated behaviour) and, well, wanting to eat the baby (her hunger). She starts by squeezing the baby’s head – really a small watermelon – as if about to crush it, before stopping herself and glancing guiltily at the audience. And then, almost by stealth, she takes her stiletto heel and grinds it into the melon-head. Before you know it the head has been broken open and Brown is consuming the red flesh inside. Suddenly seized with awareness of what she’s done, she desperately attempts to piece the head back together, hoping no one will notice.

The sequence is the most daring and transgressive in the production, playing with the tension of raw, animal hunger versus societal conditioning. Eating babies is wrong, clearly but she’s hungry – and she’s an animal and there is flesh available. What is her first priority: decorum or dinner? Brown manages to convey this dialect wonderfully.

The horror then spreads to a final sequence that is far more abstract and – at least for me – unclear. Anderson lies on his back while red starfish are projected across his naked torso. I’m not sure whether he is being consumed by the other passengers or ravaged by the sea or both. Meanwhile, in the darkness, Marchenski eats what looks like a glowing orange. Is he eating the other two passengers; has he “won”, is he the survivor? The whole conceit is so abstract that it works against the horror of the situation. I would have found it creepy enough to just listen to the sound of Marchenski’s lips slapping in the darkness.

With the heavily stylized ending, Leaky Heaven could be accused of pulling back from the real horror implied by the source material. Even the use of a melon for the baby’s head softens the impact of Brown’s scene. What I’ve written makes the sequence sound far more ghoulish than it was during performance. Did Steven Hill, the director, and his co-creators have a responsibility to go further? Would I have, in their position? I’m honestly not sure. It would have certainly made the production more graphic and involved us in a deeper level of horror. But maybe that’s another show.

In fairness, the production doesn’t set out to directly recreate the physical reality of the raft. The raft itself is simply evoked with four large inner-tubes and a pallet. These are castaways in a very dry ocean (a terrific joke to that effect is included, where the “chorus”, Jordan Bodiguel, cleans up some spilt water with paper towels, an assiduous nod to health and safety). With the exception of a few sequences when the characters crowd onto the pallet, there is no sense of the claustrophobia or the physical torment they must have endured. Much of the horror – for example the bodies of those caught in the wreckage – is only relayed in narration by Anderson. There is even an extended sequence – perhaps a collective hallucination – where the four characters sit at a dining table, in ragged clothes, alternatively despising, lusting for and ignoring one another. This brilliantly realized scene was really the core of the piece: they weren’t so much trapped on the raft of the Medusa as trapped at the worst dinner party – ever. With only crackers to eat and saltwater to drink.

Although the power dynamic at play between the characters – the men fight for control of the raft and the crackers, the women fight over the men – is a bit predictable, it is handled with great invention and humour. The cast is uniformly excellent and there are many highlights of physical humour, including Brown’s arse moving like a magnet towards Marchenski. Podlozniuk also deserves recognition for her ability to channel pissed off and create physical distance between her and the other performers that screams “victim, eat me.”

As with all Leaky Heaven shows, much of the wonder is created by a mixture of physical movement and the simplest of stage magic and is filled with many striking moments. Particularly memorable is Peter Anderson trapped below a frantically waving piece of long, thin plastic. This simple effect eerily recreates the look of being trapped underwater. Anderson then pokes his arm through the plastic, followed by his head, as if emerging from the sea.

After that, we’re on dry land and the dinner party. Not so much the Raft of the Medusa as the Discreet Charm of the Bourgeois with some baby as an appetizer.

Bone in Her Teeth, Leaky Heaven Circus, directed by Steven Hill,

performed by Peter Anderson, Sasa Brown, Billy Marchenski, Tanya

Podlozniuk with Jordan Bodiguel; Dramaturgy by Heidi Taylor; Research

Dramaturg Michele Valiquette; Music by Veda Hille, performed by

Chrisariffic; Lighting by Stephan Bircher; Set by Molly March; Costume

by Catherine Hahn; Video by Candelario Andrade; Sound by Jeremy Waller.

The piece was written collaborative by the company. At the Russian Hall

until June 1.