Arts Umbrella's Byrd Dance and Snow: questionable socks and emergencies

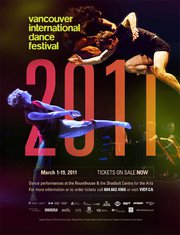

A large portion of Vancouver’s most celebrated dancers received at least part of their training at Arts Umbrella. Ranging in age from 15-18, their youth company (made up of 36 dancers) trains five days a week in ballet and modern, with two days a week devoted to creation of performance pieces. Eight of the programs (I can’t bring myself to call it a company since they don’t get paid) brightest students performed on the free stage at VIDF last night in two quartets.

The first piece, Byrd Dance, was choreographed by James Kudelka. It featured three male dancers (Jed Duifhuis, Scott Fowler, and Christoph Von Riedemann) and one female dancer (Kiera Hill.) It was a piece all about manipulation – the girl and one of the boys had a relationship with each other. The other two boys acted as their puppeteers, controlling every move the couple made. These ‘controllers’ drove the two dancers together and then pulled them apart. Tangled them up and unwound them. It was an interesting concept and I wondered if Kudelka would have treated the work differently had he choreographed on a more mature group of dancers.

The students were just that – students. The legs didn’t always fully extend, the connections between them were sometimes sloppy, the movement wasn’t as grounded as it should have been (I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again – socks/dance shoes are the enemy of the contemporary dancer.) That being said, for their age they were all phenomenally talented with strong technical training, and I’m sure they each have bright futures as performers ahead of them. These performance opportunities are fantastic experiences for them along the way. The free stage at VIDF had two huge wooden beams on either side and watching the dancers try to navigate around these obstacles was a perfect example of these young artists learning while the performance was happening.

The choreography was based on the dancers being in constant contact with each other and the piece suffered to some degree because of this limitation. They were forced to childishly hold hands for a large portion of the work and I longed to see their bodies connect in other ways. When those few moments happened, they were immediately standouts. There were moments when the controllers were instructed to add dance steps into their walking. Sometimes these additions were small attitudes between steps, sometimes they were oddly Celtic triplets which looked silly and just didn’t feel vital to the piece. This seems to happen constantly in ballet performances – the choreographer feels obligated to showcase technique so much that they lose sight of what makes sense to the work. Moments like these only served to draw me out of the moment and made me remember I was watching a performance. The clearest example of this was during my favourite scene of the piece - the controllers stepping back for a moment to let the main couple interact on their own. This was a welcome relief from the two being incessantly maneuvered by outside forces. Then, just as I became totally engaged the controllers tore them apart again, and suddenly the girl was in a full penche. Maybe it’s just me, but being torn away from the one I love doesn’t generally make me feel like doing an arabesque. Obviously classical technique is important, but these steps thrown in for no reason didn’t resonate the way a more natural reaction would have.

The costuming was also a bit distracting, and not just because of the footwear (when I asked WHY SOCKS? during the post-show talk, Artemis Gordon, head of the dance program at Arts Umbrella said that socks "complete the line of the foot." I know that sounds like a plausible excuse, but I wasn’t sure it was true since the dancers were wearing black tights and white socks) and for some unknown reason the girl is in pointe shoes. Because in the piece she was constantly being manhandled, we never actually saw her do anything on her own en pointe, which made the shoes feel irrelevant and made her seem weak, which was obviously not the case. What made the costumes especially strange was that the dancers were wearing ‘rehearsal’ clothes – white tank tops and black shorts or tights. This non-costume costume made them all look like equals but there was supposed to be a clear separation between the controllers and the dancers. The costumes didn’t help make the distinction clear.

It was exciting to see this many boys on stage at once, and were are all very well trained in partnering and so on. Every dance studio on earth should have the kind of boys-only program that Arts Umbrella has. However, I did get the feeling, especially toward the end of the piece, that the boys were being favoured and the girl was being neglected. This seems to be an increasingly common thing in the dance world. Male dancers are sometimes hard to find, extremely talented ones even more so. It seemed as if having all these capable men in the room, Kudelka started to overlook his female lead and so for a few moments during the piece’s finale she shoved to the back while the two controllers lifted the other man above their heads.

If Byrd Dance favoured the men, it was in stark contrast to the piece that followed it. Snow featured four girls dressed in short white virginal dresses. They entered the space and began to dance in unison in the dark. As the percussion of their feet on the floor started to build the music came up. It was ferocious and loud and pulsing, with a woman who sounded strangely like Penelope Cruz shouting things about freedom and emergencies. The lights came up to show the girls performing an almost tribal set of flings and jumps. These jumps looked like they were supposed to be free, but I didn’t get the sense that any of the performers were prepared to let their centers go and let gravity and momentum take over. They remained a bit too solid through their cores and I wanted to see more release.

It was an ambitious piece – I wondered if it was my imagination that the piece seemed more mature than the students, but afterward we were informed that it was in fact a remount. The choreography had originally been set on choreographer Andrea Miller’s company Gallim Dance. Again, I had to wonder how the choreographer feels setting a piece on teenagers as opposed to older more mature dancers. Kudelka’s piece didn’t seem to push his dancers beyond what they were comfortable with, but Millers piece found the girls in many positions that made them appear uneasy and vulnerable. I loved it. I wanted more. It was another interesting contrast between the two pieces.

My favourite image here occurred when three of the dancers moved to the back of the stage. Facing the back, they started to groove in unison. I found myself moving along with them, it was infectious. They brought this energy across the stage and it was lighthearted and fun amidst the banging drums and Penelope Cruz shouting about freedom and emergencies. I much preferred this energy because otherwise the piece seemed ready to become nothing more than one more page in the book of teenage angst.

I debated whether or not to stay for the artist talk as I generally find them insufferable. This one started off no differently. I tried not to roll my eyes when questions like “does it hurt when you drop to your knees?” and “where is Arts Umbrella based?” were asked. The final question of the evening convinced me that staying was the correct decision. When asked about the concept of Kudelka’s piece, Gordon said that when she asked the choreographer what it was about, he refused to give a straight answer. “It is what you think it is” was his response. Gordon listed off a few possible meanings -- were the two controllers acting as alter-egos? Were they gods? Were they parents? Thinking about the piece in this way made me want to see it again.