The Body Eclectic: A Study in Experimentation

The array of choreographers included in the latest EDAM presentation The Body Eclectic was intriguing enough to draw me from my abode: Jai Govinda, Artistic Director of Mandala Arts and Culture; Emily Molnar, former Frankfurt Ballet superstar; and Peter Bingham, contact dance guru.

There are very few dance companies in Vancouver that have not experimented with Bingham at EDAM. EDAM offers training and workshops in contact dance, a form which focuses on improvisational kinetic experimentation. The company is also known for the many creative collaborations it has encouraged over the years by giving dancers the physical space to rehearse in as well as the creative tools to investigate new movement. EDAM then presents these explorations to the general public. Although not all the work produced in The Body Eclectic featured contact dance, Bingham introduced the evening of presenting new work within a general context of allowing choreographers to explore and push their creative boundaries.

The first piece was The Monk and the Courtesan, performed by former Ballet BC dancer Chengxin Wei (I know ladies, stop swooning…), his wife Jessica Jone and Paromita Naidu, a graduate of Mandala Arts and Culture. Wei and Jone are both trained in classical Chinese dance from the Beijing Dance Academy, while Naidu is trained in the classical Indian dance form bharata natyam under the tutelage of Jai Govinda. Live music was performed by multi-instrumentalist Neelamjit Dhillon, and accompanied by the chanting of Kalpana Prasad and Jai Govinda.

The fusion of classical elements is gorgeous at times, and witnessing Wei and Jone’s experimentation with bharata natyam is stimulating. Certain elements of both forms worked well together. For instance, both classical Chinese dance and bharata natyam feature elaborate hand gestures and intense facial expressions. As I am not an expert in either form, it is fascinating to decipher where one begins and the other ends. Unfortunately, the choreography overall seems awkward, capturing intricate symmetrical tableaux at some moments while leaving the dancers in the lurch to fill the space at others. The piece yearns for serious dramaturgy – although the story of the monk and the courtesan contained the how, it lacked the why. Still, I look forward to seeing where this piece could go, and hope to see further developments.

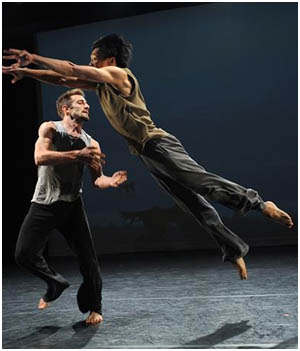

The second offering was Peter Bingham’s What is Left is Right, performed by Chris Wright and Jacob Cino. Performed against a backdrop of projected mountains and water, Cino and Wright expertly jam, using their weight and strength to guide each other into unexpected movement. Fortuitous body configurations are always the delight of this form, as is the case with Cino and Wright’s clever adventures in this piece. At one point Cino’s head suddenly supports Wright’s lower back, at another they perform parallel solos driven by the guidance and weight of their pointed index fingers.

Alas, somewhere mid-way through the piece I remember why I have held back from attending an EDAM performance for so long: although experimentation can be an incredibly valuable tool for dancers and choreographers, it does not always make for the most exciting performance from an audience perspective. At best, I find contact dance to be like watching the Grateful Dead relentlessly continuing to jam and going nowhere in the process. At worst, performances can feel like a school recital, with supportive family and friends making up an uncritical audience, enthusiastic even if the work is presented after too brief a creation period. Although I appreciate the skill and artistry that goes into both the performance and choreography, I find the overall lack of unified vision and direction frustrating.

Nonetheless, watching a couple of guys hurl their sweaty bodies at each other has its moments, and I managed to keep myself entertained, if only briefly.

Two pieces and two long intermissions later, we eventually get to see the two Emily Molnar pieces: Time Tell, set on the dancers of the Arts Umbrella Professional Training Program, and Fragments of a Marked Space, set on Chengxin Wei with his second appearance and Jennifer Clarke, known around Vancouver for her dance skills and her shock of long, red hair.

The choreography in Time Tell is intricate, broody and challenges the dancers, propelling them from one side of the stage to the next in quick, complex patterns. Molnar works well with the studio’s unfortunate lack of wing space, lining those dancers who are not performing a section along the walls in a pattern that evokes a firing line, while the remaining Arts Umbrella protégés perform solos or duets in the middle of the configuration. Fragments of a Marked Space explores the physical space between dancers. Throughout the piece Wei and Clarke alternate between pushing each other away and holding each other close, complete with pained looks on their faces. Unfortunately, this leads the piece to border on the edge of a caricaturized I-love-you-I-hate-you theme, but the dancers seem so truly passionate about each other I almost blushed at times.

I have to admit that my notes get a little blurry at this point . It was either the warm studio, the calm whirring of the fans, the dark and sumptuous James Proudfoot lighting, or the endless tinkle tinkle of the Arvo Pärt. Either way, I found my mind wandering to thoughts of Southern France, whether or not I should consider taking French classes at the Sorbonne, fields of lavender… all of which, I’m pretty certain, had absolutely nothing to do with Molnar’s choreography. Am I a fair-weather contemporary dance fan who can’t make it through two hours of experimentation? ‘Fraid so.

As I biked home in the enveloping darkness, I thought about that issue of experimentation, and ruminated over the question: at what point does experimentation end and presentation begin? In principal, I appreciate witnessing the budding stages of development. However, as a staunch fan of intensely rehearsed, well thought-out, dramaturged work, I have a short attention span for watching what is in essence a piece in the early stage of creation but which is presented as a final product. One of the pieces in The Body Eclectic was created in less than 40 hours. Who benefits from this type of presentation more, the artist or the audience?