Shadow Machine: flawed but haunting

Shadow Machine, the latest work by Co. Erasga (presented at W2 Storyeum from Oct 21-30), is described in broad strokes in its press materials, as “an exploration of the conflicting relationships humanity has held with machines and the industrial process since the first years of the industrial revolution.” Based on this ambitious description, I expected the performance to examine technological evolution in a large sense, and anticipated an evening of strangely morphed bodies and surreal technological experiments. While Shadow Machine did indeed feature inventive sets and mechanistic choreography, the narrative elements of the work were more idiosyncratic and more firmly grounded in human experience than I had expected. The quirky humanism of the piece was at times refreshing and at other times frustrating in its predictability.

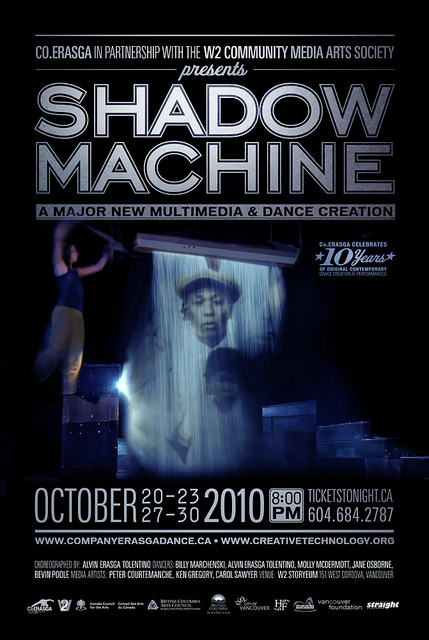

Featuring five dancers (Jane Osborne, Billy Marchenski, Molly McDermott, Bevin Poole, and Alvin Egasga Tolentino) Shadow Machine applied concepts of movement drawn from labour, machinery, and industrial culture to human bodies. Projections played a major role in the piece, from blueprints to images of sawmills and log booms to the faces of anonymous workers cast in lurid greens and yellows. These images grounded the work in an eclectic series of specific historical moments.

I found the opening portion of Shadow Machine compelling in its abstraction: two technicians manipulated laptops and voice to create an eerie ambient soundscape. Into this haunting mix of sounds – running water and metallic hammering – entered the dancers, flowing around each other in abstract spiral patterns. Enigmatic images – geometric, half-recognizable shapes drawn in white chalk on a blue ground – flickered across hanging screens. In this moment the dancers' motions suggested algebraic patterns – strange symmetries that had more to do with mathematics than human culture.

At other points, human experience weighted more heavily in the mix but with less dramatic effect: in a segment devoted to Maritime culture, dancers hauled on thick ropes, coiling them around their bodies in actions that suggested the work of a fishing culture. Bird cries and water sounds accompanied the dancers who moved cooperatively to gather the heavy lines. While lovely, I found this segment less interesting than the opening, because it seemed to lean so heavily on a romantic vision of the past. Where the opening moments of Shadow Machine were surprising and layered, these felt predictable.

Likewise, the later projections of log booms and early steam ships felt like pure Canadiana. While I am fan of the idea of digging into local history, there was a sense of nostalgia to this portion of the performance that belied its promise to explore the “conflicting relationships humanity has held with machines.” When the dancers deconstructed an old style waltz and moved in unison dragging heavy shovels across the floor, the choreography -- while not literal -- was quite obviously connected to the imagery on screen, and lacked interpretive depth.

More interesting was the final movement, where dancers repeatedly climbed a pair of steps in order to fill a high trough with shovel-fulls of granular powder. As the substance fell from the trough, it created an ephemeral sheet onto which black-and-white photographs of faces were projected. This portion of the performance fused contemporary technology, archival material, and an innovative set-piece to great effect. As they rushed from the pile of powder to the trough, the dancers were reduced to elements in a larger expressive whole, becoming simple mechanical parts of a monstrously beautiful structure. As the culmination of the “shadow machine” this segment was thrilling and unique. It is unfortunate that as a whole, the work did not consistently achieve such creative heights.