Exotic Sounds in your own Back Yard

In welcoming the audience to Vancouver Intercultural Orchestra’s production Imagined Worlds: Intertwined, VICO founder Moshe Denburg made reference to the tremendous variety of musical worlds that arise out of this “uniquely Canadian” musical setting, where master instrumentalists of diverse musical heritage foment bonds that run deeper than political and geographic differences. This is not an easy task, even for highly trained musical specialists. Music comes out of our deepest sensibilities, and, like language, it resounds in our identities in profound ways. For the intrepid musical explorer, there are few better ways to experience the world—apart from physical travel—than to hear the various musical styles and instruments that speak of foreign places and exotic timbres.

There was a time, not so long ago in dog years, when exoticism was the target of many cultural critiques. The love of something that appealed purely because it was something new to the listener, something other from elsewhere, unbesmirched by global pop culture, was questioned along the lines of cultural tourism. Then Paul Simon went to South Africa, recorded Graceland, and Peter Gabriel and WOMAD and the Realworld label came, and exotic became popular, with all that diverse talent given the studio production stamp of Western approval. It became the multicultural mainstream, and World Music started sounding familiar, no matter where it originated. And eventually it passed into fad-dom, as all Western fashions do: World music today is little more than the shadow cast by Lady Gaga.

Studio production eradicated the rawness of the ethnic soundscape from world music and from ethnomusicological sensitivity—a rawness that is vivid in the pioneering field recordings carried out by the likes of David Lewiston and Moses Asch of Nonesuch Explorer Series and Smithsonian Folkways labels respectively. Listening to these recordings is like tourism, it’s like being there, listening in person. There is a fine line that divides the appreciation of diversity from the love of exoticism with all its native soil, dirt and grime in the background sound; a line so fine it’s imperceptible to my naked ear. When the indigenous sounds of particular places travel, make contact, and settle in a new field, we get backyard diversity. Diversity grafts traditions, generates new species of music—hybrids, mutants, an entanglement of cultural left-overs that embody fecund possibility. Diversity propagates emergent varietals; it fosters new strains, rather than, as exoticism does, clinging to traditional motifs and melodies valued for their authenticity, or conversely, succumbing to the World Music mainstream, which achieves, despite its geo-political differences, an impressive conformity.

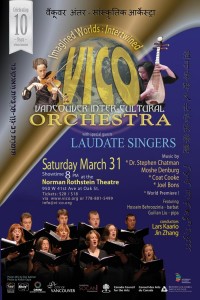

What I heard at “Imagined Worlds: Intertwined’, seemed to go one continent further, it took elements of ethnomusicology and World Music, tradition and hybrid, anthropology and musical tourism, and blended these into a profoundly diverse evening’s entertainment. Were it not for the talent of the players this concert could have been an intolerable cultural gongshow. In an evening that premiered three commissioned works by Joel Bons (Amsterdam), Stephen Chatman (Vancouver) and Coat Cooke (Vancouver), using up to 25 musicians and the 23-member Laudate choir, along with traditional pieces by played by pipa soloist Guilian Lui and a small ensemble Persian musicians led by Hossein Behroozinia, VICO took us on a guided listening tour of a new world of composition. It was a lot for one evening, a bit like watching the world by peering through a keyhole at a passing Olympic parade.

Wei Shui Qing, a tradition piece for solo pipa, placed us in the drama the Orient, with Guilian Liu’s stunning technical mastery full of almost bluesy interpretive gestures, bending notes until almost broken, weeping, all fingers plucking strings in cascades of notes that seemed to conjure a Classic Western movie chase theme, of galloping horses that pause for the resonance of a single sustained tone to appreciate stunning vistas before galloping off again. This was followed by the second traditional number, Baad, meaning Wind, played by an ensemble featuring two drums, two bowed-string kamanches, and two lute-like instruments, the tar and oud. This piece varied from a sweet, calm breeze emphasized by stroking the drum skins, wafts of melody from the bowed strings, to a driving sandstorm with both hand drums thrumming the 17-beat rhythmic structure, all musicians turning a trance-inducing dynamo that made the heart race to hear it, an adrenalin rush, that would just as abruptly drop down to a whispering draught again.

Those two numbers summed up the traditional aspects of the evening before we began to hear hybrid musical forms take shape. We immediately transitioned to the world of Western Art Music, heavily influenced by the European avant guard. Bons’ composition “Green Dragon” extolled the virtues of the diversity of instrumental sounds VICO encompasses, choosing paired string instruments of different traditions. While introducing his composition, Bons had each musician strike or hold a note, thus comparing the Western violin and cello sounds with the Persian tar, santur, the Chinese zheng, pipa and erhus. With my eyes closed, Bons’ “Green Dragon” was reminiscent of Sequenza-era Berio, or Stockhausen, and it was odd to open my eyes and see the multicultural assortment of musicians on stage. Very little trace of the Near and Far Eastern traditions remained when brought together by Bons. I found the piece hauntingly even-tempered, constrained, calculated, and deliberate: it was exciting and arresting to hear the Western avant guard conjured with such an exotic assortment of instruments.

Moshe Denburg also contributed a composition that evoked the classical Western worldview, with an older piece titled El Ginat Egoz (Into the Walnut Garden) based on the text of the biblical Song of Songs. Denberg’s composition, a gentle, melodic piece for three instruments including erhu, zheng, and marimba, seemed a delicate structure to support the large choir that sang the words. Indeed, at times, the voices drowned out the three traditional instruments that accompanied them, in swells of passion that sought rapturous release. Although it was earth hour, Denburg had the house lights brought up so that we could read along, which was an unnecessary gesture—perhaps we should care for the world we have and enjoy the piece with our ears only, I thought, rather than bring our same old problems and habits into an imagined world. However, the composition did not lack in de-light, even with the lights on.

The second half of the program began with Coat Cooke’s composition Invocation for S’Unduda, a reference to the composer’s youthful discovery of musical joy and the source of his name, Coat. S’Unduda, he explained, means the best of all possible worlds—friends, feasts, and freedom to follow one’s own path through the world. Much of this spirit of the piece came through in his conducting (Cooke was the only composer to also conduct his own piece), which looked like he was playing and having fun with the musicians, encouraging them to improvise with a sense of irreverent joy. The piece had a number of different parts, some scored, some improvised, and featured a central solo by Bie Hoang on the danbau. While there were moments of cool fusion-phase Miles Davis / Teo Macero moods throughout, Hoang’s solo turned the temperature up, and propelling the sentiment invoked in the piece, the danbau solo had the power of Jimi Hendrix’s crying, left handed guitar licks to invigorate and expand musical consciousness.

S’Unduda transitioned from chilling spaces, to cool interplay of parts, to hot-tempered, even irascible moments of pure ecstasy. Although incorporating elements of improvisation, this composition seemed to move from section to section with precision and never strayed into free jamming. Taking a trick out of the experimental jazz tradition from which Cooke hails, he had the musicians occasionally dispense with the normal way of playing their instruments. According to Denburg, Cooke’s composition pushed VICO’s players out of their comfort zones and off in new musical directions. It was, overall, the crowning achievement of the evening and brought the traditional habits of the musicians and their instruments into a fresh space of spontaneity and connection, working a new magic spell to produce chimerical effects: Wondrous, strange, yet reminiscent of jazz before it, too, became over produced and saccharine as Kenny G and mochachillos. My only regret is that Cooke’s composition, like Bons’, did not have the opportunity to make use of the choir. While not too out of the ordinary for Bons’ influences, the freeing jazz influence might also have moved the Laudate choir to new musical sensitivities.

The final composition for the night was an intercultural musical treatment based on the text of Omar Khayyam’s Ruba’iyat composed by Stephen Chatman of the UBC School of Music. While ultimately sounding like a movie musical, Chatman’s approach was a bit like a mash-up of all traditions. In one movement, he prepared us for a ragtime rendition of the sufi text, at other times it took on a Broadway-esque modality and gave full vent to the magnificent voices in the choir, featuring soprano soloists Heidi Ackermann and Catherine Crouch. Even with the full cohort of VICO musicians, the choir’s presence took over. All styles and individual traditions seemed to fold into the thick, taffy-like consistency of Chatman’s compositional style. What we gained from Cooke, the freedom to enjoy each stringed, skinned, or blown thing swirling around in its own sound, we lost with Chatman’s big sound, which swallowed up distinction and difference, it was at times fanfarish, not meditative, which seemed an odd choice for Omar Khayyam’s famous poem, which was chosen as tribute to a elderly friend (who was in attendance) for whom the Ruba’iyat has been a lifelong inspiration, rather than because of a special affinity that Chatman saw between the musical opportunity provided by VICO and the poet’s words. Chatman introduced his piece saying that this was the greatest compositional challenge of his life. He must have worked very hard to have all those disparate elements fuse into something that was the melting pot to Cooke’s mosaic version of the intercultural society.

By the end of this two-hour concert we had covered nearly 20,000 Earth miles. I had supersonic jet lag, but also the sense that I’d not just traveled, but had also discovered something unexpected, a new world of possibility. VICO, now in its tenth year as an organization, is a marvelous project not only because it encompasses such diverse talent among the cadre of musicians, but because, under Denburg’s guidance, it is going to undiscovered places and imagining new worlds. It is astounding that this re-imagined art has roots in our local backyard. It is Vancouver’s soil and noise that gives rise to this rare and spectacular species of entertainment. If you ever start feeling tired with contemporary, mass, over-produced culture or feeling a lack of optimism with the direction the good old Earth is heading, VICO has just what you need to see the cup as half full again, with room for sumptuous music, the possibility of discovery—exploration without the imperialist overtones that have made homebodies of high-seas orchestral adventurers.