Edge Two: shining brilliantly through

Edge Two, part of this year's Dancing on the Edge Festival, featured a program of four diverse dance pieces.

Winterfall

Choreographer: Lisa Hostman

Performers: Vanessa Goodman and Amy Tao

This was a finely wrought, tightly wound dance for two women. Wearing modest, knee-length dresses in earthy pink and indigo, Vanessa Goodman and Amy Tao begin at opposite ends of the stage, the former looking out on the audience. Slowly she seems to discover her own limbs, moving her arms in short jerky motions – as if she were a wind-up doll – and tapping her own head from side to side, like the clapper of a bell. These are rigid and delicate movements, informed as much by ballet as by any throwing-off of constraints that belongs to Modern Dance.

The graceful and yet oddly mechanistic attitude of these opening gestures is then transposed into the duet proper: Tao and Goodman treat each other's bodies like classical instruments. Goodman lifts her partner under the arms and slowly swings her body back and forth while Tao articulates delicate steps around her. Tao grasps Goodman by the head and makes a lifting motion, as if drawing out some malignant spirit, performing a blessing or a cleanse. The collaboration is nuanced: though they both give over to the manipulation of the other, neither partner is passive. Together they construct a language of movement that is as fine as tatted lace.

A kind of exquisite suffering was expressed; the dancers so intertwined, so passionate but restrained. In their final moments, Goodman stands behind Tao and while supporting her by the neck slowly lowers her towards the floor, until Tao is suspended in a half-moon posture. Goodman looks towards the ceiling, and, as if listening to an inner voice, releases her hand and walks calmly away. Tao is left alone on stage, looking limp and painfully contorted, like child's forgotten doll.

With low, raked lighting and a sweet, minimalist score selected from the works of Sigur Ros and John Beaulieu – songs that hover somewhere between lullaby and a wind-up music box – the ambiance was one of stained innocence. “Oh my virgin ears” one might say in response – and not mean that the sounds were painful, but that one felt as if something infinitely delicate was in the midst of being broken.

This One's for You Dad

Choreographer: Meredith Kalaman

Performers: Amanda Sheather and Meredith Kalaman

In absolute contrast to the opening work, This One's for You Dad was a raucous rambunctious journey through the best of Queen. Firmly tongue in cheek, the piece made merry with the conventions of Glam Rock. The fact that the performers were women in drag – dressed in long frizzy wigs, cut-off shirts splashed with AC/DC and Rolling Stones logos, track pants and aviator sunglasses – only highlighted the campy queerness of their forever-young rocker personalities. High-macho, crotch-grabbing and air guitar suddenly became hysterical posturing when taken up by ironic female dancers. Repositioning rock tropes – a stereotypical masculine fantasy – in a dance setting –a stereotypically feminine arena – This One's for You Dad satirized the youthful nostalgia at the heart of the musical genre with and a deft hand.

The success of this piece lay in the supreme confidence with which Amanda Sheather and Meredith Kalaman performed their parts. Had they danced with less conviction, their role-playing would have fallen flat. They rose fearlessly to the challenge of ensuring that the audience got their fix of air guitar. They gave of themselves selflessly and when the occasion called for it, they thought nothing of whipping off their track pants to moon the audience (at some length) with the shiny prosthetic asses hidden underneath.

Though humour is unquestionably at the core, Kalaman's choreography deserves serious consideration for the ways she carefully scrutinizes human body language. For instance, during the chorus of a particular song, the dancers made motions with their hands – as if they were peddling small, invisible bicycles, or doggie-paddling through an imaginary lake. Such moments of sheer oddity lent humour, but more than that, contributed to the ways that the work offered commentary on its subject. Perhaps no glam rocker would make such movements, but somehow the movements are still appropriate to glam rockers. Kalaman strikes a pleasing balance between the familiar and the strange, proving that even in the context of a spoof, contemporary dance can still be experimental; it is still a way of exploring ourselves and coming to know ourselves more fully.

To see the world through the eyes of a thoughtful choreographer is to have the commonplace things of the world taken up and returned to you a little askew, with oddities enhanced, emotions sculpted and writ large, so that what lies below the surface suddenly shines brilliantly through – sometimes quite literally.

Slam2

Choreographer: Serge Bennathan.

Performers: Vanessa Goodman, Jane Osborne, Leigha, Wald

Slam2 exposed the audience to a choreographer's unique vocabulary: movements that were simultaneously athletic and agile, heroic and eccentric.

The work incorporates enigmatic scraps of parable and literary allusion with a highly polished series of movements. The dancers do not enact the narrative – spoken intermittently by each of the three performers into a microphone hanging over a corner of the stage – and neither does the narrative enact the dancers' journey. Instead the two elements create a complex overlay, like looking at two slides projected one atop the other: the resulting fusion is not easy to decipher, and certainly does not yield to literal interpretation, but the whole is rich with metaphoric possibility.

Dressed in loose fitting tunics and trousers in shades of soft gray, yellow, and brown, the dancers are introduced to the audience as voyagers: we never know where exactly the travelers have been, or what is “the village” that they refer to as home. Much is made of the arduousness of their journey, the need for great bravery and feats of strength, the trials they face as they pass through alien towns. The words spoken to this effect offer a key-hole glimpse into the meaning of the gestures, as the dancers use their full bodies to express their strength, their fear, their courage, and their cleverness. What is most refreshing about this fusion of dance and narrative is the sense that bodies have been liberated from the conventions of conversation: a performer will use her torso or her legs to express surprise, joy, excitement as readily as she uses her hands or face. Though the work is theatrical, it belongs wholly to dance.

Also powerful is the balance that the choreographer strikes between the yin and yang of dance: the performers read as both actors in a drama and as pawns of more powerful forces. They contort themselves as if struggling with great emotion, struck by lightning or tormented by an angry god, but they are also proud and fierce when they swagger across the stage. The overall effect is epic. The story of these Odyssean wanderers is greater than any one individual, but the individuals themselves are more than equal to the challenge of playing on a hero's stage.

Finally, one must also note the warm and sensual elements of the drama. One phrase turns up repeatedly: “a silk scarf bought at great expense in the city – at least that's what he said.” Never fully contextualized, the phrase nonetheless acquires resonance through repetition, speaking to the exotic charisma that a returning wanderer holds for his more domestic peers.

Slam2 is a poetic parable of adventure and return. That it is highly allusive, non-linear, and challenging to interpret speaks to the confidence of its creator, who permits images and fragments to stand on their own, inviting the audience to enter into this difficult construction and make what they will of the parts.

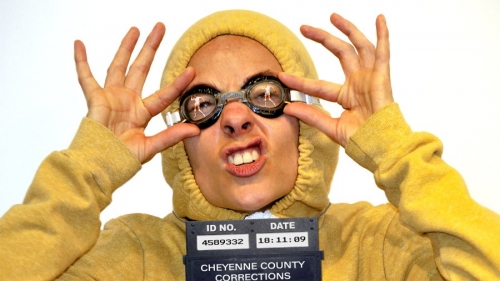

Goggles

Choreographed and performed by Tara Cheyenne Friedenberg

Friedenberg performed an excerpt from Goggles, a piece she will present in its entirety at The Cultch in November. Dark, hair-raising electronica composed by Mark Stewart sets the stage for what is described in the program as the company’s “newest comic creep-fest.” Goggles more than lives up to this description.

Appearing onstage clad all in yellow, hooded, and wrapped in a pair of thick goggles, Friedenberg morphs into a creature of stunning physical complexity. Her character, Norman aka Goggles, notable for his nasal voice and obstreperous chatter, is identified (in Friendenberg's promotional Youtube broadcast) as a precocious, troubled eight-year-old obsessed with true crime drama. He is all this and much more. He is the archetypal loner: this spastic form recalls every semi-autistic boy-wonder, every post-apocalyptic mad scientist, and every lunatic-fringe schizophrenic ever depicted in pop culture, from the Delicatessan's sewer-dwelling “troglodytes” to the haunted film-noir personalities of Blade Runner. A disordered psyche constantly in the process of destroying and rebuilding himself, this Goggles (as we first see him) is as alien as Ziggy Stardust, though vastly different in character. Luminous on a dark stage, he is like a diver alone in a black ocean. At times funny and childish, he still possesses the bleak, isolated spirit of the Fool on the Hill: nobody seems to like him / they can tell what he wants to do.

However, the audience is pushed beyond pretty metaphors of mystic outcasts: obsessed with unsolved murders, Norman is addicted to all things macabre. Bloodthirsty and motor-mouthed, he has the soul not of a poet but of a hardened forensics expert.

In her opening moments, Friedeberg's motions suggest a body that cannot control its own behaviour – a figure at war with himself and his limbs flail constantly, of their own accord. As the narrative builds– with Goggles/Norman chattering merrily about Rorschach blots, bloody fingerprints, and cadavers – Freidenberg's jerky movements begin to gel into a compelling whole. Like a DJ looping tracks, she creates a powerful blend of speech, slapstick, physical comedy, and several forms of contemporary dance. In doing so she displays her profound mimetic prowess. The result is a work near-cubist complexity.

Alone on the stage, the already fragmentary personality of Norman transforms himself many times over: now he is the forensics investigator dipping a finger to taste the blood, now he is the first body, now the second. Now he is the knife that stabbed a victim. Now he is both the bullet and the bullet wound. There is something transcendent in what Friedenberg does: her body is the stage and the prop and character. But it is always the dancer's body: fluid, expressive and independent of all literal figuration.

If a DJ creates a soundscape, Friendenberg creates an image-and-word-scape: a fusion of spoken drama and dance that is more than the sum of its parts. Moment to moment, Norman speaks, emotes, expresses but he is never allowed to run too long in one groove. His movements and words revolve around themselves, cut away and back to themselves. There is no resolution, only a constantly mounting of tension as Norman's murder-mystery fantasies reach a climax.

In the last portion of the excerpt, Friedenberg leaves words behind. Having carried the audience so far into Norman's shadowy imaginings, having developed a vocabulary of physical signs, a code for us to follow, she gives over to the music and simply dances; and somehow, this dark art is beautiful.

Even in an abbreviated form, this was an exceptional work of performance.